Issue Essays & Rebuttals

Topic: School Vouchers

|

Issue Essays & Rebuttals Topic: School Vouchers

|

| <<Return to School Vouchers Page | ||

The Argument

For...

Contributed By Gordon Jones

[Click here to learn about

Gordon and our other contributors]

My reasons for supporting Referendum #1 fall into four areas:

1. A philosophic bias in favor of freedom. In general, I think

the free choices of individuals in markets produce better

results than decisions made in the political system. I believe

that the competition that comes with choice produces better

results all around.

The research seems to bear out that judgment. Where school

choice has been tried, not only do those opting for private

schools do better in school, but the students remaining in the

public schools also do better. The U.S. Postal Service has

vastly improved its service under (fairly limited) competition;

no reasons schools shouldn’t do as well.

Of course for most choices I do not advocate government

subsidies for private choice. But where a decision (to educate

all children) has been made societally, the mechanisms used to

implement that choice should be as market-oriented and free as

possible.

2. The question of an efficient delivery system to attain a

societal goal brings up the question of costs. Utah faces a 30

percent increase in the number of K-12 children over the next 10

years. Utah already has the lowest per-pupil expenditures in

the nation, and the highest pupil-teacher ratios. Those numbers

will worsen inexorably unless we try something different.

On average, Utah spends $7,500 per K-12 pupil per year. The

average cost of an education voucher is anticipated to be

$2,000. If one can purchase $7,500 in savings with the

investment of $2,000, that is a deal one should take.

Anticipating a couple of objections here, let me point out that

since we are talking about future growth, the “fixed costs”

argument does not apply. (In truth, it never did apply; the

growing areas of, say, southwest Salt Lake County have been

“draining” students from east-side schools for generations, and

taking full funding with them. Charter schools “drain” students

from traditional schools in the same geographic area, taking

less than full funding but almost twice what vouchers will

take. The schools on the east side and where charters exist

have managed to make the adjustments just fine.)

Another objection is that $2,000 (or even the maximum voucher of

$3,000) will not cover private school tuition, so the

economically-disadvantaged won’t be helped. The average private

school tuition in Utah is $4,000, so $3,000 will certainly help,

and it will completely cover tuition in many private schools,

particularly the schools that exist in lower-income areas.

Here are some numbers of interest: Total annual education

spending in Utah clocks in at around $3.5 billion dollars.

First-year cost of the voucher program is estimated at $9

million. Fully phased-in (after 13 years) annual cost of the

voucher program is estimated (by voucher opponents) at about $70

million, which would mean that 35,000 students were taking

advantage of it (out of a school-age population then of

something in excess of 650,000), saving the taxpayers $262.5

million, for a net savings of about $190 million a year.

True, some of those 35,000 would be students whose parents would

have sent them to private school anyway, which reduces the net

savings somewhat. Total private school enrollment today is

around 15,000. That number will also grow, so let’s use a

number of 20,000 private school students 13 years from now. If

we were to subtract out that 20,000 and project a diversion of

only 15,000 students as a result of the voucher program, the

savings would still be $112.5 million, or a net $42.5 million

per year.

Sidebar: My recollection is that Utah has about 20,000

teachers. Those annual savings could mean more than $2,000 a

year to those teachers. Alternatively, you could take the

savings and hire 1,400 new teachers, reducing class sizes from

25 to 23. Per pupil expenditures would go up by $65. We’d

still be last, nationally, but we’d be better off than we are

now. End Sidebar.

No doubt there will be some wealthy families that will take the

$500 voucher to reduce the cost of Waterford from $13,000 a year

to $12,500. Another sidebar: The argument is often made

that this program will take from the poor and give to the rich,

but that is obvious nonsense. The poor don’t pay taxes,

particularly if they have children. The rich are already paying

far more in taxes than they are ever going to be able to recoup

with a $500 voucher. The program might take from the childless

rich and give to the fecund rich, but the current system already

does that. End sidebar. Far more numerous will be those

stuck in the worst schools on the west side, who will be able to

take a voucher of $3,000 and use it at a private school,

increasing their range of choice and saving the rest of us

money.

3. Those are the people at whom this program is aimed, those

without the resources to exercise choice today. After all, if

one is a millionaire, one can already send one’s children to

private school if one wants to. But if one is trapped by

economic status in an area of failing schools, one has few

options. And the persisting gap between majority and minority

achievement rates is one of the most glaring failings of the

public schools. That gap would be worse were it not for a

dropout rate that also impacts most heavily those of limited

income.

The appeal of school choice is driving leadership at the

national level to the minority community. Leading voucher

proponents have included Polly Williams, Floyd Flake and Bernice

Gates, leaders in their minority communities, and now the

irreplaceable Howard Fuller, with his

Black Alliance for Educational Opportunity.

In years past, many “liberals” recognized the advantages of

school choice for minorities. Hubert Humphrey said

“I favor the creation of

a tax system where parents would be able to receive a tax credit

when their children attend approved private schools.”

Pat Moynihan: “I

do not think that the prospect of change in this area

[education] is enhanced by the abandonment of pluralism and

choice as liberal ideas and liberal values. If that happens it

will present immense problems for a person such as myself who

was deeply involved in this issue long before it was either

conservative or liberal. And if it prevails only as a

conservative cause, it will have been a great failure of

American liberalism not to have seen the essentially liberal

nature of this pluralist proposition.”

Cleveland Mayor

Michael R. White (who is black, BTW):

“We’ve got to stop having

a knee-jerk opposition to school vouchers and charter schools. .

. . For all the African-American officials that have come out

against vouchers, you will never find my name.”

Robert B. Reich: “The only way to begin to decouple poor

kids from lousy schools is to give poor kids additional

resources, along with vouchers enabling them and their parents

to choose how to use them.”

The Salt Lake Tribune supported school choice until a couple of

years ago: “One way to [stop UEA bullying] would be to offer

Utahns educational choice. Let state education subsidies

accompany each child to whatever school the child happens to

attend, regardless of whether that school is public, private or

parochial.

“This way, UEA members will be focused on improving the schools

in which they teach in order to keep children in them. This way,

whatever resources come their way will be based on how well they

teach, not their ability to bully.”

Democrats in Utah often argue that they are unfairly stigmatized

as “liberal.” Here’s a chance for them to use a truly “liberal”

issue to illustrate their case. But though Bill Orton favored

school choice when he ran for governor, not a single Democrat in

the legislature supported it (including Duane Bourdeaux, who

sent his children to private school).

But aren’t private schools likely to be segregated? How can

minority leaders and parents support that? It would be hard to

find schools more segregated than Utah’s, but studies nationwide

indicate that private schools are in fact more integrated, and

that the behavior of their students is less racially-motivated.

That is, they voluntarily mix more in lunch rooms and at recess.

And this might be a good time to address the “creaming”

argument, that private schools will siphon off the best

students, leaving the “dregs” for the public schools. After

all, the public schools have to take everyone, and private

schools can pick and choose.

Again, the facts don’t bear out this fear. While there are no

doubt some “exclusive” private schools, private schools as a

whole have a more diverse student body on any metric one could

care to name, from race to economics to physical and mental

handicaps and behavioral problems. The public school system

already contracts with a number of private schools to educate

students with certain mental and physical handicaps, and with

certain behavioral problems. These arrangements constitute, by

the way, a “voucher” program, just as the Carson Smith

Scholarship program does.

Voucher opponents try to have this “creaming” argument both

ways. Harvard researcher Caroline Hoxby has found that when

choice is increased, academic performance goes up

both for the students moving from public to private schools and

for the students who remain in the public schools. Since

these are aggregate numbers, she notes, some might try to argue

(some in fact have) that the reason public school scores go up

is not because the public schools improve, but because the worst

students take advantage of choice and leave, causing the average

of the remaining students to jump. Hoxby somewhat dryly notes

that critics can make this “anti-creaming” argument if they want

to.

4. Social tensions. My fourth reason for supporting school

choice is really a derivative of the first: my belief that

markets avoid social tensions in ways that politics cannot.

Politics is a zero-sum game. When a decision is made

politically, one side wins and one side loses. In markets, both

sides win.

Translating that idea to education, consider “Investigations

Math,” as implemented in Alpine School District. Some parents

swear by it, others swear at it. But when the decision is made

politically, one is either going to have it or not have it, and

one side is going to win and the other side is going to lose.

The bitterness of the battle has been prominently on display in

recent years.

With school choice, both sets of parents can win. Those that

want Investigations Math can have it; those that want Saxon math

can have that. Tensions are lowered and civility can prevail.

The range of tension-inducing subjects is large (and growing)

and frankly, I see school choice as the only way to avoid broad

unrest and increasingly bitter political battles. Some of these

are subject matter-related, such as mathematics and reading

instruction methods; others are sex education, creationism v.

evolution, drivers’ ed, the presence or absence of music (and

whose music—John Cage or Mozart?) and the arts (and which

arts—Vagina Monologues or Mark Twain Tonight?), vending machines

and campus demonstrations.

*

* * * *

In one sense, the majority of Utahns have had the best of both

worlds for a long time. Education has been provided at taxpayer

expense, and yet it has essentially been delivered by a

relatively homogeneous school system closely mirroring the

dominant socio-religious culture. That is less true today, and

in my opinion less true than most members of that dominant

socio-religious culture think.

In the final analysis, school vouchers are likely to have less

of an impact than either side imagines. Right now, fewer than

three percent of Utah’s school children are in private schools.

The national average is 13 percent. No matter what happens, for

the foreseeable future 90-plus percent of our children are going

to be in the public schools. If we can use vouchers to effect

some modest savings, and at the same time introduce some

innovation through competition, it seems to me that we should do

so, even if there is no immediate, measurable benefit to the

vast majority of us.

For the children of the less fortunate, this is not a small

matter.

Scroll Down for

Rebuttal

|

The Argument

Against...

Contributed By Craig Johnson

[Click here to learn about

Craig and our other contributors]

On November 6th, Utah voters will decide whether to

put their stamp of approval on a flawed voucher bill or to send

it back to the legislature.

Some say “just give it a try,” which begs the reply “have they

actually read the bill?"

You’ve seen the ads and heard the soundbites. But you’re not

here for soundbites. The fact that you are reading this article

– along with my opponent’s remarks – is evidence that you care

enough to thoughtfully consider this issue. I applaud you for

this and thank Nick Ramond for creating a site that provides

this opportunity.

Aside from the philosophical arguments pro and con, in which

legitimate and credible points from good folks are raised on

both sides, the bill itself is what we’re actually voting on.

And the bill itself has problems – serious problems. As more

voters become educated on the actual bill, flagging support has

further dwindled with voters rejecting the bill by a nearly

two-to-one margin, according to the latest Dan Jones/Deseret

News poll.

Listed below are three of the reasons voters find the bill so

troubling:

The bill provides far too

little accountability for taxpayer funds

In other voucher programs such as those in Florida, Ohio, and

Wisconsin, accountability has been an Achilles’ heel. Lack of

accountability has left legislators and other public officials

in these states to bemoan the greed, fraud, waste, and abuse

that have accompanied their state’s voucher programs.

They’ve recognized, only too late, that once a bad precedent is

established the resulting problems are extremely difficult to

repair.

A

quick Google search yields many troubling examples. As recently

as yesterday (10/17), two Florida private voucher school owners

were convicted of

swindling over $200,000 from state and federal programs,

including purchasing a Hummer and another car for themselves

using voucher funds.

Given the experiences in other states, it would stand to reason

that a Utah bill would seek to prevent these abuses.

Unfortunately, just the opposite is true. The Utah bill has

even fewer financial controls, curriculum requirements, teaching

and licensure requirements, and accreditation requirements than

these other flawed programs. And, unlike other states, the Utah

bill is universal, encompassing the entire state regardless of

income, NCLB status, or special needs.

Instead of addressing the lack of accountability, the Utah bill

would make matters worse.

As a member of a state charter school committee (charters are

free, public schools of choice), I am keenly aware of the recent

governance and fiscal problems with a few of the charters around

the state. Fortunately, these problems are addressable by state

charter school officials. Like all public schools, Utah charter

schools are subject to state open meeting laws and to sunshine

laws such as GRAMA. Public neighborhood and charter schools are

also required to post 3rd-party audits each year and

those audits are freely available for public review. Spending

decisions are made under the purview of a watchful public eye.

But this is not the case for private voucher schools. They can

operate in a cloud of secrecy. Most of the folks I talk to are

shocked to discover that the private voucher schools that would

receive hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars would have no

such transparency under this bill. While it is certainly true

that a dissatisfied parent can leave the private voucher school

and take their business elsewhere, this single measure of

accountability is only part of the equation. Parents and

taxpayers expect proper controls of public dollars to be

established. The failure of the bill to enforce even basic

minimum standards for the proper use of funds is an almost

certain guarantee to create wealth where it’s not deserved and

victims where it could have been avoided.

The good judgment of parents to leave a bad-fit school will not

prevent fraud and abuse of public funds. Those controls rest

with our elected officials and public auditors. And while many

schools would act appropriately, this alone is not a sufficient

reason to pass legislation that hands abusers a blank check on

the public’s nickel. Utah has the ignominious reputation as the

fraud capital of the United States. Passing a voucher bill with

even fewer protections than other states is just a really bad

idea!

For a quick summary of the differences in accountability between

public schools and private voucher schools, please review the

link below:

http://www.utahnsforpublicschools.org/facts/public_vs_private.php

While proponents will seek in their upcoming newsletters to

dismiss these concerns as “Halloween scare tactics,” these

problems are real. They’re happening now in other states and

the Utah bill would set the scene for an even larger mess.

*****************

The bill costs far more than it

saves

This is a simple fact and proponents’ claims to the contrary are

either incomplete or are based on grossly overblown speculations

of the number of students who might switch to private schools.

To bring some sense into the discussion of costs vs. savings, I

would recommend reviewing the impartial analysis of Referendum

1. This analysis, conducted by the Lieutenant Governor’s

office in partnership with Legislative Fiscal Analysts (the

folks who assess the financial impact of legislation), concludes

that the voucher bill will cost taxpayers hundreds of

millions of dollars.

The impartial analysis is required by law to be impartial.

Either side may challenge the language or the conclusions.

Neither side did.

Yet this hasn’t stopped voucher proponents from attempting to

discredit the impartial analysis. Paul Mero of the Sutherland

Institute went so far as to call for the elimination of fiscal

analyses for referenda and ballot initiatives.

Some important details of the impartial analysis can be found in

the official voter information guide. In the guide, you can

see, for instance, that in the 13th year of the

program the estimated cost is $71 million while the savings

estimates range from $11-$28 million. This yields a NET COST to

taxpayers in the 13th year of $43-$60 million.

Over the course of the 13-year

phase in, the total net cost

to taxpayers for the program (total costs - total savings) is

estimated at $164-$334 million.

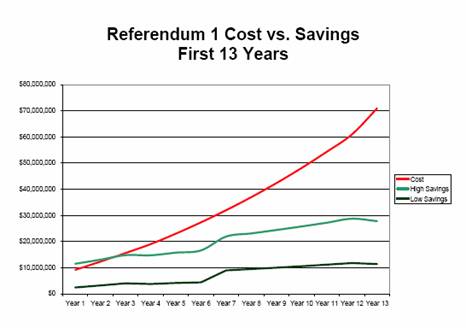

The graph below shows the costs and savings of the program as it

is phased in. The escalation of costs results primarily

from paying vouchers to an increasing number of private school

students who never intended to go to public schools in

the first place.

(Source of data – Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst)

The “red line” of the graph demonstrates the costs of the

program. The “green line” represents the best possible cost

savings (it assumes no fixed costs for the switchers), while the

“black line” represents the lowest possible savings (it counts

only WPU expenditures).

While proponents will claim that these are simply “estimates”

(so how can we be sure of anything, etc.), such a line of

thinking is unwise. To achieve even a break-even on the bill,

the Legislative Fiscal Analyst would have to be off by hundreds

of millions of dollars. This is unlikely. These folks analyze

hundreds of bills per year – they’re pretty good at what they

do.

If you’ve seen the “cookie stacking” ads from the pro-voucher

side, you may wonder how this all plays into the debate. Simply

put, the savings mentioned in the ads are represented in the

“green line” of the graph. But, as you can see, this is just

one piece of the overall picture.

Some pro-voucher proponents claim that the bill would save as

much as 1.8 billion dollars. This is terribly misleading.

These numbers refer to the cost of educating all current and

future private school students over the next 13 years should

they all suddenly decide to attend public schools. Closing down

all of the private schools and absorbing those students into

public schools is a silly notion and is not what’s on the

ballot. It is a red herring argument.

Proponents are expecting voters to count the difference in what

we would have spent on all private school students vs. the cost

of vouchers as some sort of savings. But this cannot be, for we

are currently spending $0 to educate students who always

intended to go to private schools. Fact is, paying vouchers to

such students represents a new cost to taxpayers.

To provide clarity, the impartial analysis demonstrates

the complete picture of costs

vs. savings. The bottom line – over the course of the

13-year phase-in, this bill demands an increasing amount of

taxpayer funds to pay vouchers to students who never intended to

go to public schools. This creates neither competition nor

savings. Over the phase-in, the bill would result in a

new, unnecessary private school funding mechanism, paid for by

taxpayers from state sales tax revenue, to the tune of $164-$334

million.

Proponents may choose to support vouchers for other reasons but

the impartial analysis makes it clear that taxpayer savings is a

false argument.

*****************

The bill is an empty promise

for most low and middle-income families

According to official state figures, the average tuition for one

year of K-12 private education is just over $8,000. This is

very different from the $4,000-$4,250 number used by pro-voucher

proponents. To arrive at the smaller numbers, you must exclude

ALL private high schools (proponents only count K-8), then

remove the 6 or 8 most expensive K-8 schools (depending on who

is doing the calculations) and finish by calculating the

capacity-weighted median of the remainder. In their ads and

charts, proponents then contrast this massaged number against a

fully burdened $7500 cost of public education, K-12, all schools

included, whether special ed or breezy mainstream, whether urban

or rural, whether brand new or fully paid for. It’s an

inaccurate and misleading comparison.

Truth is, official state figures show that public schools are

less expensive than private schools. This stands to reason,

given the economies of scale we enjoy with public education.

Private school attendance at a quality school is expensive.

Most low and middle-income families, even with a voucher, would

not be able to afford a quality private school. The graduated

amount of the voucher depending on income ($500 to the wealthy

and up to $3000 for those who qualify for free or reduced lunch)

does help level the playing field somewhat. But the fact

remains, under this bill, that the probability that a wealthy

Utah family who can already afford private school will use a

voucher is far greater than it is for a low or middle-income

family. With increased access comes increased usage; simply

put, those with greater discretionary incomes would use vouchers

far more than would those with lower incomes.

The exceptions – those low and middle-income families who might

benefit from a sound, accountable voucher program – are the

victims in the crossfire of this bad bill.

Consider private initiatives such as the admirable efforts of

Children First Utah, a non-profit organization offering private

school scholarships. These groups serve a legitimate purpose –

to offset expensive private school tuition for low-income

families.

Legislators would have been wise to pattern the voucher bill

after the qualification requirements of Children First Utah.

CFU enforces a strict income cap, based on family size, to

qualify students for their program.

But with the voucher bill, even millionaires qualify for a $500

voucher. There is no cap. Strange but true. If the bill were

truly about helping those who couldn’t afford private school, it

wouldn’t be handing out vouchers to those who can already easily

afford it.

When tuition, fees, books, supplies, transportation, and lunches

are factored in, the final bill for one year of education at a

quality private school remains out of reach for far too many low

or middle-income families, even with a graduated voucher. The

bill fails in its lack of reach at the lower end and its overreach

at the higher end.

And to add to the irony, you may recall that vouchers would be

paid for by state sales taxes. All of us, whether rich or poor,

pay state sales tax. Such gives rise to a “Prince John”

scenario (an inverse-progressive tax) – taking from the poor to

pay for the rich. Proponents try to cover this up, too, saying

that poor folks don’t pay taxes. But we all pay sales tax – the

would-be source of voucher funding as specified in this bill.

On a personal note, I find it curious that the same legislative

forces pushing this expensive voucher program couldn’t come up

with $2 million for preventive care for elderly, blind, and

disabled Utahns.

The Utah voucher bill is the only such program in the history of

the United States without an income cap. It hands out money to

those who don’t need it and is an empty promise for too many

Utah families.

*****************

On a final note, I’d like to emphasize that although this bill

has serious problems, the vast majority of Utahns support the

mainstream philosophical arguments of both sides. This

bodes well for our future. I applaud the good people who

support excellence in education. Competition, market

involvement, and offering a range of options are noble and

important values that have helped make America great.

Other ideas, such as cooperation, the social contract, and

opportunity for all are also cherished values in our society.

It would be a shame for this bad bill to cause greater divisions

of good people on both sides. While I value the good work

and good ideas behind the intent

of the bill, the bill itself does not serve the best interests

of Utah families. The bill must be rejected. And I

believe it will.

I

urge you to vote AGAINST Referendum 1. Let’s vote down this bad

bill, and, together, work toward real solutions and real reforms

to improve the educational opportunities for all of Utah’s

schoolchildren.

(Source of data – Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst)

The “red line” of the graph demonstrates the costs of the

program. The “green line” represents the best possible cost

savings (it assumes no fixed costs for the switchers), while the

“black line” represents the lowest possible savings (it counts

only WPU expenditures).

While proponents will claim that these are simply “estimates”

(so how can we be sure of anything, etc.), such a line of

thinking is unwise. To achieve even a break-even on the bill,

the Legislative Fiscal Analyst would have to be off by hundreds

of millions of dollars. This is unlikely. These folks analyze

hundreds of bills per year – they’re pretty good at what they

do.

If you’ve seen the “cookie stacking” ads from the pro-voucher

side, you may wonder how this all plays into the debate. Simply

put, the savings mentioned in the ads are represented in the

“green line” of the graph. But, as you can see, this is just

one piece of the overall picture.

Some pro-voucher proponents claim that the bill would save as

much as 1.8 billion dollars. This is terribly misleading.

These numbers refer to the cost of educating all current and

future private school students over the next 13 years should

they all suddenly decide to attend public schools. Closing down

all of the private schools and absorbing those students into

public schools is a silly notion and is not what’s on the

ballot. It is a red herring argument.

Proponents are expecting voters to count the difference in what

we would have spent on all private school students vs. the cost

of vouchers as some sort of savings. But this cannot be, for we

are currently spending $0 to educate students who always

intended to go to private schools. Fact is, paying vouchers to

such students represents a new cost to taxpayers.

To provide clarity, the impartial analysis demonstrates

the complete picture of costs

vs. savings. The bottom line – over the course of the

13-year phase-in, this bill demands an increasing amount of

taxpayer funds to pay vouchers to students who never intended to

go to public schools. This creates neither competition nor

savings. Over the phase-in, the bill would result in a

new, unnecessary private school funding mechanism, paid for by

taxpayers from state sales tax revenue, to the tune of $164-$334

million.

Proponents may choose to support vouchers for other reasons but

the impartial analysis makes it clear that taxpayer savings is a

false argument.

*****************

The bill is an empty promise

for most low and middle-income families

According to official state figures, the average tuition for one

year of K-12 private education is just over $8,000. This is

very different from the $4,000-$4,250 number used by pro-voucher

proponents. To arrive at the smaller numbers, you must exclude

ALL private high schools (proponents only count K-8), then

remove the 6 or 8 most expensive K-8 schools (depending on who

is doing the calculations) and finish by calculating the

capacity-weighted median of the remainder. In their ads and

charts, proponents then contrast this massaged number against a

fully burdened $7500 cost of public education, K-12, all schools

included, whether special ed or breezy mainstream, whether urban

or rural, whether brand new or fully paid for. It’s an

inaccurate and misleading comparison.

Truth is, official state figures show that public schools are

less expensive than private schools. This stands to reason,

given the economies of scale we enjoy with public education.

Private school attendance at a quality school is expensive.

Most low and middle-income families, even with a voucher, would

not be able to afford a quality private school. The graduated

amount of the voucher depending on income ($500 to the wealthy

and up to $3000 for those who qualify for free or reduced lunch)

does help level the playing field somewhat. But the fact

remains, under this bill, that the probability that a wealthy

Utah family who can already afford private school will use a

voucher is far greater than it is for a low or middle-income

family. With increased access comes increased usage; simply

put, those with greater discretionary incomes would use vouchers

far more than would those with lower incomes.

The exceptions – those low and middle-income families who might

benefit from a sound, accountable voucher program – are the

victims in the crossfire of this bad bill.

Consider private initiatives such as the admirable efforts of

Children First Utah, a non-profit organization offering private

school scholarships. These groups serve a legitimate purpose –

to offset expensive private school tuition for low-income

families.

Legislators would have been wise to pattern the voucher bill

after the qualification requirements of Children First Utah.

CFU enforces a strict income cap, based on family size, to

qualify students for their program.

But with the voucher bill, even millionaires qualify for a $500

voucher. There is no cap. Strange but true. If the bill were

truly about helping those who couldn’t afford private school, it

wouldn’t be handing out vouchers to those who can already easily

afford it.

When tuition, fees, books, supplies, transportation, and lunches

are factored in, the final bill for one year of education at a

quality private school remains out of reach for far too many low

or middle-income families, even with a graduated voucher. The

bill fails in its lack of reach at the lower end and its overreach

at the higher end.

And to add to the irony, you may recall that vouchers would be

paid for by state sales taxes. All of us, whether rich or poor,

pay state sales tax. Such gives rise to a “Prince John”

scenario (an inverse-progressive tax) – taking from the poor to

pay for the rich. Proponents try to cover this up, too, saying

that poor folks don’t pay taxes. But we all pay sales tax – the

would-be source of voucher funding as specified in this bill.

On a personal note, I find it curious that the same legislative

forces pushing this expensive voucher program couldn’t come up

with $2 million for preventive care for elderly, blind, and

disabled Utahns.

The Utah voucher bill is the only such program in the history of

the United States without an income cap. It hands out money to

those who don’t need it and is an empty promise for too many

Utah families.

*****************

On a final note, I’d like to emphasize that although this bill

has serious problems, the vast majority of Utahns support the

mainstream philosophical arguments of both sides. This

bodes well for our future. I applaud the good people who

support excellence in education. Competition, market

involvement, and offering a range of options are noble and

important values that have helped make America great.

Other ideas, such as cooperation, the social contract, and

opportunity for all are also cherished values in our society.

It would be a shame for this bad bill to cause greater divisions

of good people on both sides. While I value the good work

and good ideas behind the intent

of the bill, the bill itself does not serve the best interests

of Utah families. The bill must be rejected. And I

believe it will.

I

urge you to vote AGAINST Referendum 1. Let’s vote down this bad

bill, and, together, work toward real solutions and real reforms

to improve the educational opportunities for all of Utah’s

schoolchildren.

|

|

| A Rebuttal... From Craig Johnson [Click here to learn about Craig and our other contributors] My opponent’s article highlights his personal economic preferences and includes some social commentary. It’s an interesting read and I commend my opponent for a well-written philosophical piece. But it has little to do with the bill we’re about to vote on. As citizen-legislators, our job is to consider the bill before us and to make an informed decision based on facts. My opponent speculates on the costs vs. savings of the bill in wild opposition to the impartial analysis as performed by the Legislative Fiscal Analyst. I leave you to judge which numbers are unbiased. In my article, I presented three grave flaws in the bill – poor accountability, unnecessary high cost, and failure to help most low and middle-income families. Any one of these flaws is sufficient grounds to reject the bill. Ironically, however, the bill also fails to support the market forces arguments raised by my opponent. Let’s review: As the impartial analysis indicates, the skyrocketing costs of the Utah bill as it is phased in would come from paying vouchers to those who never intended to go to public schools in the first place. Such choices are pre-determined. And as any economist will tell you, subsidizing pre-determined choices does not create competitive pressure since it does not alter any outcomes. These parents have already made up their minds to send their children to private schools. There is no point in handing out vouchers to them since it does nothing to influence other schools to improve. We would be spending hundreds of millions of dollars in new, unnecessary costs and receiving no competitive benefits whatsoever in return. This makes no sense. But what about the switchers, proponents ask? Let’s begin with those switchers who would have switched anyway without a voucher. Again, we would be paying out vouchers for no reason. As it stands now, any competitive pressure induced by their departure is already realized. With vouchers, this market force doesn’t change. The only thing that’s different is that we would be spending money – millions of taxpayer dollars – unnecessarily. So, that leaves us with the switchers who would leave because of the voucher. We’ve already spent hundreds of millions of dollars just getting to the point where we might see some competitive forces at work. Was it worth it? Do public schools actually improve because of vouchers? Not really. Multiple studies show that vouchers do not make public schools better. In the New Zealand program, for example, some poorly performing schools simply became worse as they ended up with larger concentrations of difficult-to-teach students. Lawmakers, committed to seeing market forces work, ignored these schools for years. But it didn’t work and in the end they had to intercede and invest in these schools. Returning to our scenario - remember, we would have spent hundreds of millions of dollars needlessly paying for predetermined choices just to get to the point where a few switchers might exert some competitive pressure. In the bill’s impartial analysis, given the price elasticity of demand, the Legislative Fiscal Analyst determined that about 3 students per school per year might switch because of the voucher. This small switch rate is completely insufficient to force whatever improvements proponents claim the bill will generate. So this leaves proponents with only one remaining scenario to talk about – more switchers! With the flaws in the bill becoming clear and with the cost vs. savings argument debunked, we’re now starting to see the “more switchers” argument surface. Senator Bramble recently said: “One way to avoid higher income and property taxes is to offer parents the option to have their children move into the private sector and take some pressure off our public schools. That's what the voucher plan is all about.” (Emphasis added) For the bill to become effective we must somehow greatly increase the number of switchers far in excess of the impartial analysis. Proponents are now making the case that we must increase the switch rate; they’ve even raised the specter of tax increases if we don’t. Ironically, I’ve watched a couple of pro-voucher friends in the blogosphere challenge the Legislative Fiscal Analyst’s findings and try to improve upon the numbers. The result – they have switched their positions and are now voting against the bill. For the sake of argument, though, let’s discuss how this might happen. How do we convince MORE families to LEAVE the public schools? If motivating more families to LEAVE the schools is necessary for the bill to become effective, what does this mean for our public schools? Remember - it took hundreds of millions of dollars just to get to the point where we must now entice thousands upon thousands of additional public school students beyond the impartial numbers to LEAVE our public schools just to recoup the opportunity costs so the bill might exert market forces so it might create some competitive pressure so our schools might improve in spite of studies showing that this hasn’t worked when it’s been tried before. Does this sound like a winning strategy? But even if all of that does happen, just where does that leave the overwhelming majority of students who remain in our public schools? If the goal is to convince students to LEAVE the public schools, then what possible motivation do these lawmakers have to improve our public schools? If we improve our schools, we reduce demand to leave. If we reduce demand to leave, we reduce the switch rate. If we reduce the switch rate, the bill becomes an expensive failure. Why on this green earth would we set up a scenario in which the success of one program is based on the failure of another? Why would we sacrifice the quality of the public schools where 96% of our children attend just to make them SO BAD that people would WANT to leave, just so we can say this bill was not a failure? This bill makes no sense! Let’s vote it down and work together to craft real solutions. |

|

A Rebuttal... From Gordon Jones [Click here to learn about Gordon and our other contributors] “Jam tomorrow and jam yesterday—but never jam today.” -Lewis Carroll It is nice to know that there is some common ground. I appreciate Craig’s implication (though he doesn’t really say it) that those on my side of the debate “support excellence in education.” And he really does say nice things about Children First Utah, the private organization that generates scholarships for low-income students. But permit me to doubt that Craig is as positive about school choice as he claims here. I think if he really believed that “Competition, market involvement, and offering a range of options are noble and important values....” he (and the organizations with which he is associated) would at some point over the last seven years have supported some of the other efforts that have been made to provide school choice in Utah. Instead, he opposes parental choice through vouchers in ANY form. At the end of his essay he asks us to “vote down this bad bill” and “work toward real solutions and real reforms to improve the educational opportunities for all of Utah’s schoolchildren.” I’m interested to know what these “real reforms” will consist of. Will they include merit pay for teachers? Will they include alternative certification? I’m willing to bet that they will not include tuition tax credits or vouchers that would put parents back in charge of the education of their children. Will they be “jam today”? I’m dubious. This bill, says Craig, is flawed. Is there, then, a parental choice bill anywhere enacted or proposed in the United States that he could support? I have been a drafter of legislation for 30 years, and I recognize that perfection is elusive the first time. One enacts a bill whose general aims one supports, and one monitors its implementation and corrects it as necessary. One does not simply oppose it as the UEA and the rest of the education Establishment did. When Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act, the National Education Association did not oppose it, and now seeks to improve it during its reauthorization process. Conceivable including millionaires is a flaw in the bill. I have argued, and still do, that the beneficiaries of this bill will not be the millionaires, who can already afford private schools for their offspring, or who live in areas with excellent schools anyway. The beneficiaries will be low-income parents struggling to improve the lives of their children. But there certainly is a marginal benefit to the millionaire, who can qualify for a $500 voucher. Let’s correct that next February. If we do, will Craig support the bill? Craig says that Children First Utah serves “a legitimate purpose—to offset expensive private school tuition for low-income families,” and he is right, which is why I have supported CFU from its inception. But CFU cannot meet the demand. So many low-income families apply for its scholarships (which are nothing more than vouchers, financed in part by the tax-deductibility of contributions) that it has to choose the lucky children by lottery. What other flaws does the bill have? Craig cites financial accountability, a strange charge, considering that no one has yet been able to figure out what happened to $24 million in textbook money the legislature appropriated to the public schools four years ago; or considering the years-long embezzlement of funds from at least two public schools in Utah that came to light last year. The fact is that private schools accepting vouchers will undergo yearly audits. That’s more than the public schools get. No, I’m afraid it’s “jam tomorrow and jam yesterday, but never jam today.” And the fundamental reason is an unwillingness to trust parents with the education of their children. |